The Russian state wants to monitor the Internet in the country more closely than before with a law. The goal, critics fear, is to control political communication. Can it succeed?

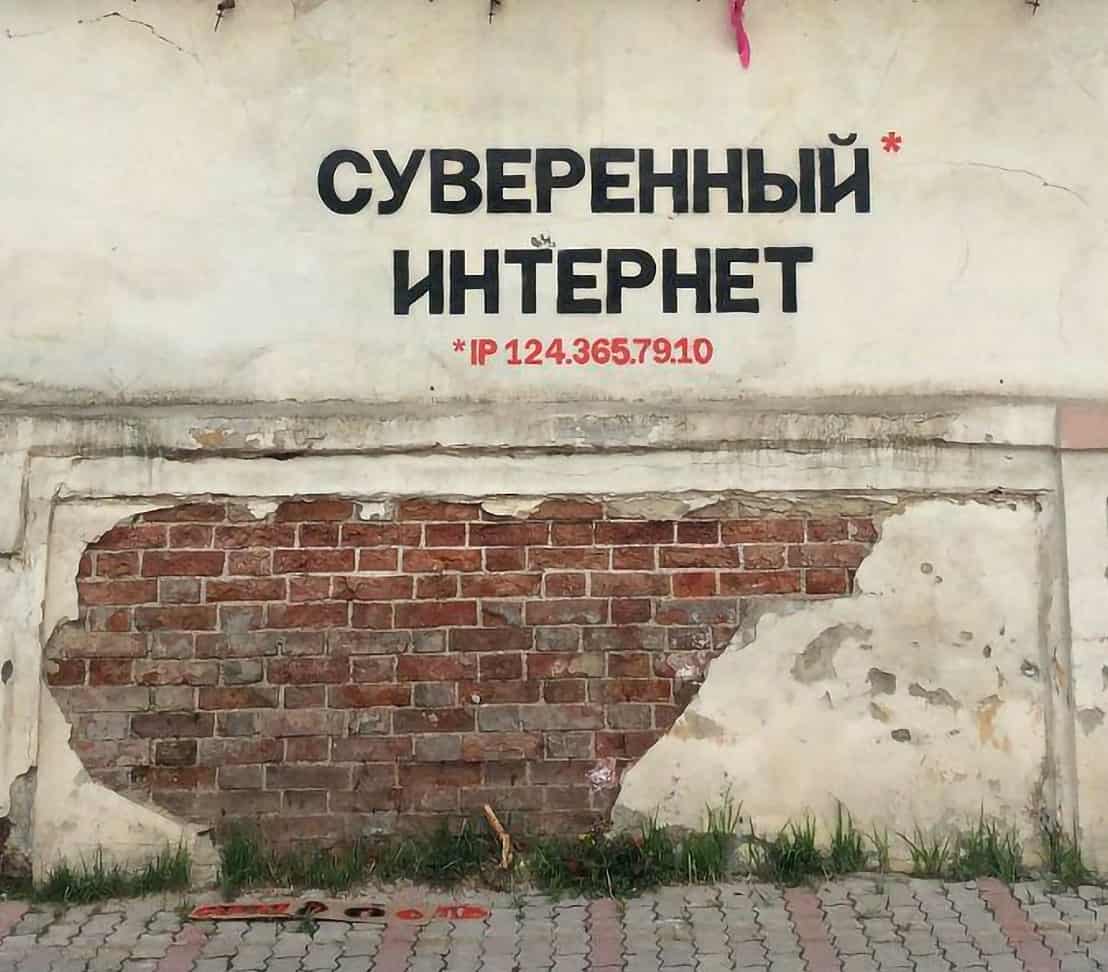

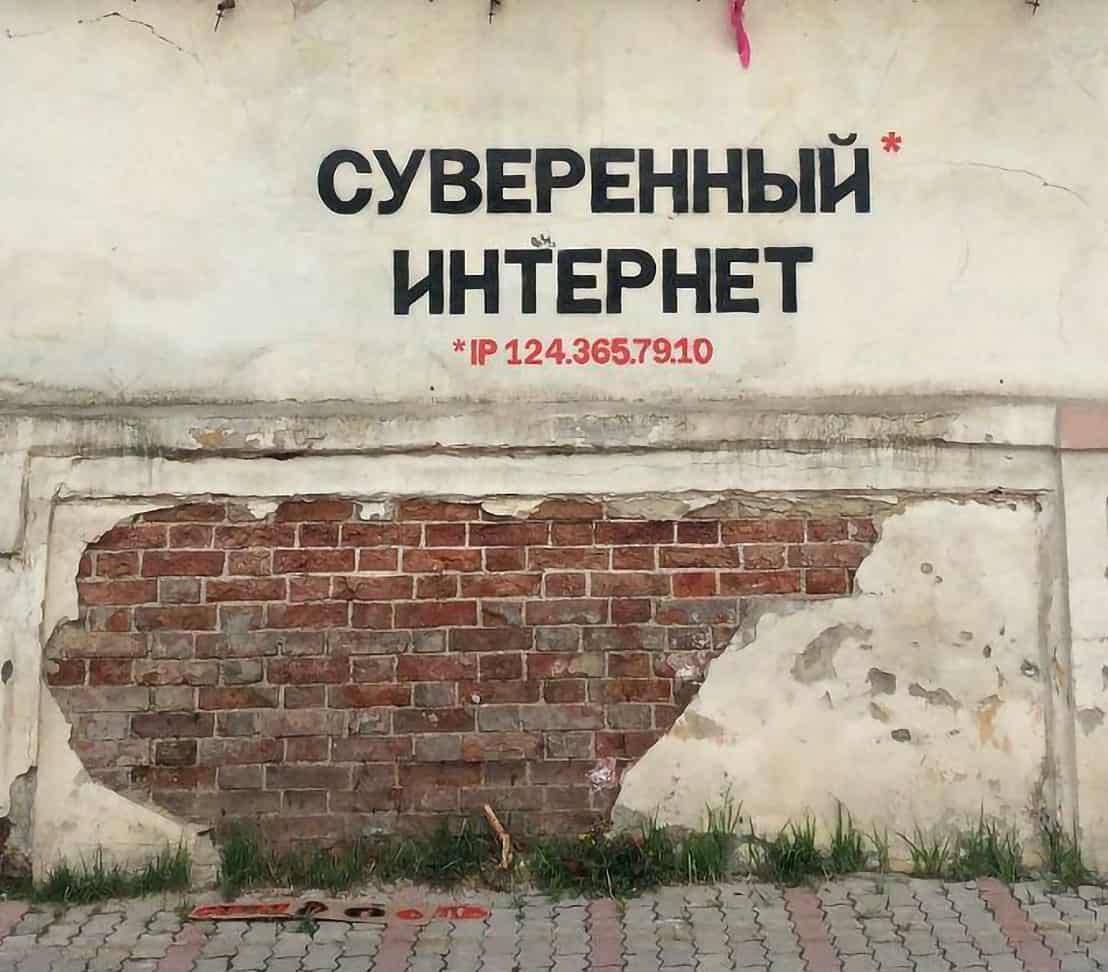

( Photo: picture alliance / ZUMA Press)

When tens of thousands of Muscovites took to the streets last summer, they knew it wasn’t going to be a walk. They protested for free elections when the state power quickly shows its hardest side. But hardly anyone had expected such a massive intervention on July 27, 2019: The number of 1,373 people arrested was not expected. One did not count on the batons of the Russian National Guard, which fell again and again on men and women of all ages. And you didn’t count on what happened to the ATMs in the city centers: they no longer worked. The cell phones of many demonstrators were also unable to dial into the Internet. The providers explained this by overloading the network. In the following weeks, some activists carried devices with them to measure the data flow precisely. By August 31, at the latest, they had the proof: The 3G and LTE frequencies were no longer available at some providers, but phone calls were still possible. The Internet was not congested. It had been turned off.

The everyday life of the protests in Hong Kong caused outrage in Russia. After all, the network was the place where Russian citizens could feel for decades the freedom they often missed in the offline world. You should understand it no later than November 1, 2019 – the day on which the “sovereign internet” law came into force.

Sovereign, so the writers of the law say, that means security against dangerous content, but also independence from abroad and its harmful influences. All internet providers have to interpose powerful filter technology with which the state can potentially monitor and manipulate every data packet. If desired, access to certain offers – such as Facebook or Google – could be restricted or blocked. In an emergency, such as during protests or before elections, according to the law, parts of the Russian Internet could even be disconnected entirely from abroad.

Critics of the law say that only the state wants to become sovereign on the Russian Internet. If the technology works, it will amount to potential total surveillance. And should it not work – which some experts assume: state-of-the-art contracts for filter technology alone are awarded, and civil servants and entrepreneurs could benefit from it. Also, the law has a symbolic effect – as the most severe attack on a free internet that has been appreciated in Russia for decades.

It is blocked today – unsuccessfully

A Friday evening in mid-October 2019, it is Wladislaw Sdolnikow’s 30th birthday. The blogger does not feel like celebrating today; he just toasts with coffee in a to-go mug before talking about the future of the Russian Internet in a small café in downtown Moscow.

Sdolnikow was one of the people who investigated, documented, published, and shutdowns during the summer protests. He is a blogger, activist, IT specialist, one of the most high-profile experts on internet blocking in Russia. It was a busy month behind him: it wasn’t just the Moscow city elections in September, in which opposition candidates were not admitted, a summer full of protests, arrests, harassment, online and offline. There was also Sdolnikov’s break with the anti-corruption initiative of Russia’s best-known opposition politician, Alexei Navalny, which he advised voluntarily for seven and a half years. He doesn’t want to burden himself with the internal intrigues and power struggles, he says.

Because the worrying thing is that it is the law of the sovereign Internet, which is to be fully implemented by 2021, there is a video recording of the first meeting of the responsible committee, Sdolnikow says: “Old, not necessarily smart people talked for an hour and a half about how best to turn off the Internet.”

Technically, it is already possible to force Internet providers to block certain offers. There is a list of IP addresses that cannot be accessed on the Russian Internet. The LinkedIn job network, for example, is not available because the US provider does not save any data on Russian servers.

If you believe Sdolnikow, the Russian state wants full control over what citizens can see and write on the Internet. “Of course, the presidential administration dreams of switching off YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook. But she also understands very well that she can’t do it from one moment to the next,” he says. On the one hand, that would cause protests among the population. On the other hand, it could currently be easily circumvented – for example, if you pretend not to be in Russia at all using VPN access.

Sdolnikow himself has shown how this is technically feasible: When people tried to block the messenger service Telegram in Russia in spring 2018, he developed the TgVPN offer. This and similar applications showed the Russian state the middle finger: you want to block Telegram? See, we’re just getting around this lock. The messenger remained functional, became even more popular; every third Russian smartphone owner now uses it.

“Old, not smart people spent an hour and a half talking about how best to turn off the Internet.”

This is mainly due to the channels that you can subscribe to on Telegram: there is one for every topic that you can imagine. Sdolnikow also has his own. With around 50,000 followers, the most successful channel on the subject of internet censorship, it provides its subscribers with the latest information. In Russia, telegram channels are part of the social media mix, just like an Instagram profile or a YouTube channel. In essence, newspapers have avenues in which they advertise their articles; celebrities share memes and holiday videos, bloggers send authentic reports, or even distribute them Hoaxes and rumors. There are political discussion groups but also channels with original and inhuman content. Everyone can write about what he or she wants, anonymously, and encrypted.

When the internet police screw up

Authorities usually have two names in Russia. An official one that hardly anyone remembers and an abbreviation. It is the same as the authority that monitors the Internet. While hardly anybody knows the “Federal Service for the Supervision in the Field of Communication, Information Technology, and Mass Communication,” the acronym “Roskomnadsor” has become a synonym for Internet police.

This agency is relatively young; it was founded in 2008 and has grown more powerful year after year. Since 2012, she has been monitoring the list of dangerous websites and has carried out bans – especially those related to child pornography, drugs, extremism, but also calls for mass protests. Some breakdowns caused a lot of malice on the Russian Internet. In 2016, for example, all offered hosted by Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Russia for a short time, from Netflix to Dropbox. The reason: only online poker advertising should be blocked. However, it was hosted by AWS. This had a fatal consequence: Roskomnadsor inadvertently blocked everything that was sponsored by AWS.

The case showed what a savage means such full closures can be. With the law on the sovereign Internet, the Russian Internet police should now have a more precise instrument at hand: Russia-wide DPI technology (DeepPacket-Inspection). With devices that every Russian Internet provider has to interpose according to the law, every data packet on the Russian Internet could be checked – sender, destination, content – and, if necessary, filtered out.

However, it is not yet clear how DPI will work on a Russian-wide scale. Roskomnadsor carried out the first DPI tests in the Urals in autumn. If you believe the independent Russian journalist Alexandra Prokopenko, the tests failed for the time being. It relies on several sources from the administrative apparatus. For this purpose, the software has already appeared that shows users whether their data packets are filtered with DPI technology. “It doesn’t look like the instruments are working,” says Prokopenko.

Above all, she sees DPI as a political tool, a tool for propaganda. The Russian leadership considers the technology to be a promise, she says, a modern solution to counter the negative feelings of the Russian population. “One way to ensure stability and increase survey values is to influence information: not just emphasize the positive, but block the negative – literally,” says Prokopenko.

Roskomnadsor now has until January 2021 to remodel Russia’s Internet. Cynics may be surprised that this has not happened before. It is not without certain humor that it is thanks to one man of all that Chinese conditions did not prevail on the Russian Internet from the start—the man who is now at the head of Russia.

It was December 28, 1999, when the Russian Prime Minister invited twenty leading representatives of the still young Runet (short for Russian network) to the White House. The name of the then 47-year-old: Vladimir Putin. He was to be promoted only three days later – and thus received the title that he still holds today: President of the Russian Federation.

The question that interested the Russian government at this meeting: Should the state control the allocation of domains? However, the Internet representatives suspected, some of them subsequently reported that the question of which controls on the Internet should be expected would also be decided. It was agreed that the less state, the better for business – and the Internet. You were successful. In the end, Putin, who probably did not see a threat to his power from the Internet, made a promise that would later be cited and should apply for more than twelve years: “We will not even seek the balance between freedom and regulation. Our choice will always serve freedom.”

What followed were the golden years of the Russian IT industry. Large companies emerged, most of them based on the American model; Yandex found its business model on Google and is now the leading search engine in Russia: almost 60 percent of users use Yandex, less than 40 percent use Google, the Yandex statistics service shows.

The social network VK is accessed three times as often by Russian users as Facebook, and the second most popular network ok.ru beats the US platform. Only Instagram has no successful Russian equivalent. Ozone is considered a Russian Amazon; the US group does not even have an independent offer in Russia.

Hardly any other country has managed to create such a large number of its own companies and offerings that, in the long term, have defied and even overtaken US suppliers – except the People’s Republic of China, whose Internet has been restrictive from foreign offers from the start was sealed off.

“The Russian Internet of the nineties shows what the Russian population is capable of if you don’t harass them,” said filmmaker and journalist Andrej Loschak in an interview. In seven episodes, over four hours in total, he traces the stories that were written in the Runet. What begins as a class reunion, in which older men remember the exciting years nostalgically, ends with the dystopian present. Large companies like Yandex or mail.ru, although they are all still highly profitable groups, yet innovative, but they are increasingly under the Kremlin’s nose. In essence, state-critical entrepreneurs are leaving the country, oligarchs with ties to Putin are securing shares in large one’s Internet companies; social networks cooperate with security authorities.

Significantly, documentary filmmaker Loschak does not meet many of his protagonists in Moscow or St. Petersburg, but in villas in Silicon Valley. Russian investor Yuri Millner, for example, who made a billion fortune thanks to the runet, explains in front of the camera that he no longer holds any shares in Russian companies. Why that was recently observed in mid-October 2019: When the Kremlin supported a bill that would limit foreign participation in Russian Internet companies, the search engine company Yandex lost 18 percent of its market value in one day. The draft was changed quickly, and the stock has been recovering ever since.

“The Russian Internet of the nineties shows what the Russian population is capable of if you don’t harass them.”

But it’s not just investors who are turning away from the Runet; many programmers are also leaving their homes. Russia’s technical and mathematical education, praised worldwide, has produced some of the best coders in the world. But now they prefer to work in California or Germany, in London or Dubai than in Russia. However, some of them continue the conflict with the Russian authorities. So also a rival of Roskomnadsor, who inflicted a painful defeat on the body in 2018: the now 35-year-old Pawel Durow.

A paper plane as a sign of freedom

It was October 10, 2006, Durov’s 22nd birthday, when he opened the window on the new Russian Internet from Saint Petersburg. VK went online that day; in the west, the offer is often disparagingly referred to like a Facebook clone. But Durow quickly developed the social network into a platform that Facebook was superior to in many ways. For example, music and videos could be uploaded and shared with friends, copyrights and Internet piracy were of little concern to Durow. VK was the place that young Russians didn’t want to leave.

So it was also the place where VK users organized themselves in groups for demonstrations in 2011. The Russian domestic intelligence agency FSB asked Durow to close these groups, given the so-called “Arab Spring.” Durow refused; in the summer of 2013, he even followed up with the encrypted messenger app Telegram; as the logo, he chose a paper plane. Pressure on Durow continued to increase until the prosecutor’s office investigated him. He is said to have injured a traffic police officer during an inspection. In April 2014, Durow sold his shares to Putin friend and entrepreneur Alischer Usmanow, resigned as CEO of VK, and left the country with his older brother Nikolai, a gifted coder and mathematician. The Messenger Telegram, however, was not to be missed

On April 17, 2018, Roskomnadsor finally decided to block Telegram. Russian providers were asked to block the requests that targeted the IP addresses of the Telegram servers. The messenger should no longer be usable in Russia. Shortly after that, both Telegram and various users tried to establish a connection via proxy servers, which in turn were targeted by Roskomnadsor. What happened in 2016 with that of AWS hosted online poker advertising occurred – only to a much larger extent, so that the Russian Internet NGO Roskomsvoboda spoke of the “IP genocide”: access to more than 15 million IP addresses was blocked, most website operators were uninvolved. It wasn’t just the websites of small and medium-sized companies that went offline. Devices in hospitals that were connected to the Internet no longer worked.

Such cases are particularly problematic about the current law on the sovereign Internet, explains analyst Alexandra Prokopenko. Because whoever is liable for damage caused by government intervention on the Internet is questionable, she says: “In my opinion, the Russian legal system is not prepared for such cases.”

Roskomnadsor is still targeting Telegram. The agency is still occasionally trying to prevent access to the messenger servers, but with small, careful steps to avoid a total IP failure like 2018. However, it is not difficult for users to circumvent this block – also thanks to VPN services such as that of Wladislaw Sdolnikow.

This example gives the IT blogger hope that the new Internet law and the associated DPI technology cannot be used effectively – and the Russian Internet is booming again, as was the case in the 1990s. “As soon as power is no longer in the hands of bandits, Russia will be one of the most advanced countries in the field of IT services,” he is sure. After all, Russia has an advantage over China: the market is simply too small. US providers like Google could afford to insist on western principles on the subject of censorship and freedom of expression. A state actor like Roskomnadsor will lose out in a cat and mouse game on the Internet.

After all, there is a mindset among many users on the Russian Internet that is said to have been developed during the repressions in the Soviet Union: Whenever a new rule is passed, think first about how you can circumvent it.