Facebook is tough on disinformation, its bosses in Silicon Valley say. Sounds good, but it’s not quite right: the social network is still the best tool for political manipulation. We reveal the four most essential tricks for right-wing and would-be autocrats.

Online advertising: who is Donald Trump’s ads? Public domain-like released by unsplash.com Darren Halstead

Facebook is increasingly playing the role of an online police officer. The social network regularly reports on new measures against manipulation, it has recently blocked extreme right-wing sites in Austria and unmasked alleged Russian fake accounts. One might think that Facebook will be uncomfortable for right-wing extremists and authoritarian governments.

But don’t worry, dear Donald Trumps of this world! We have compiled the best tips and tricks for you on how you can continue to manipulate people on Facebook and influence elections. Here are our instructions in four steps.

Step one: ask questions and ask for money

Most of us learn the trick in elementary school: a controversial claim is more natural to spread if it appears to be harmlessly packaged as a question. For example: “Can it be that Peter always steals the erasers here?”

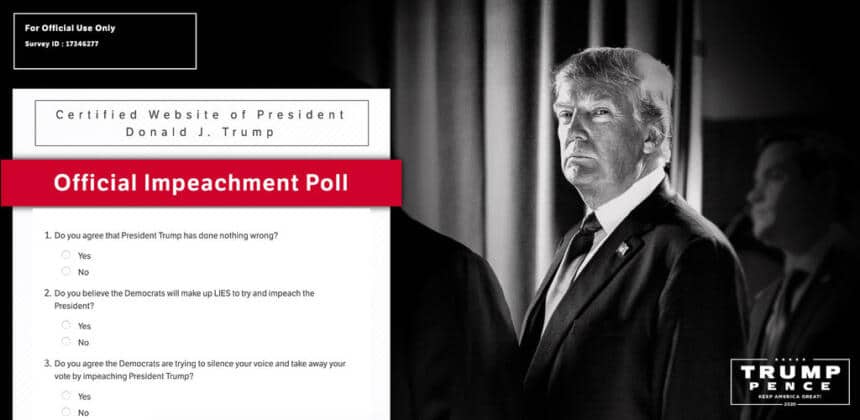

Donald Trump takes the principle to extremes. His reelection campaign is flooding Facebook and YouTube with advertising. Trump often relies on surveys. “Do you agree that President Trump didn’t do anything wrong?” Is a statement wrapped up as a question and at the same time a click-bait political statement that many Americans cannot resist.

Trump 2020: Opponents’ allegations as a fundraising tool

The Trump campaign focuses on simple messages that arouse emotions. Around 84 per cent of its advertisements call users to take action – be it a survey, the purchase of a T-shirt or a donation. An internal Facebook investigation came to this conclusion after the 2016 US election.

The reactions of the users are valuable for the campaign: Inside on surveys or donation calls: They generate new data. Emotionally charged content helps to give Trump’s messages even more attention. Trump’s sponsored posts are shared often, which organically increases their reach.

According to the Facebook study, Trump spent far more money on advertising than his opponent Hillary Clinton just before the election – $ 44 million compared to their $ 28 million. His campaign tailored the ads much more precisely to small groups (“microtargeting”), tested many different versions of the same message – and repeatedly asked voters for money.

Trump is pursuing the same strategy for the presidential election in November 2020. Hundreds of ads from his campaigns promote an “Impeachment Defense Fund”, a collection against the planned impeachment process of the Democrats against Trump. Due to political hurdles, it is uncertain whether the impeachment will take place. But Trump doesn’t care, until then he has an excellent fundraising tool.

Trump already relies on Facebook and Youtube 13 months before the election. Some Democratic opponents are far more traditional: Presidential candidate Joe Biden shows Facebook the cold shoulder and shifts his advertising budget to TV spots, reports the New York Times.

Of course, it must be said: Emotional content and microtargeting are not manipulative in themselves. But Trump shamelessly dodges racism, falsehoods, and data-driven advertising into a poison cocktail that turns Facebook into a dangerous political weapon.

Step two: tell fairy tales about your opponents

Trump tells brazen political lies. In a 30-second commercial clip, the President’s campaign claimed that his opponent Joe Biden, as US Vice President of Ukraine, would offer $ 1 billion in aid if investigations surrounding his son Hunter Biden were dropped.

Biden indeed put political pressure on Ukraine at the time. But the claim that Biden directly supported his son lacks any factual basis, according to fact-checkers at Axios and Politifact. CNN, therefore, refuses to broadcast the spot and another Trump video. Facebook and Youtube, on the other hand, see no reason for reluctance.

Trump’s Biden video: His advertising often relies on the colour combination of black, white and red

Facebook boasts of its actions against fakes and misinformation. In Europe, Facebook officially commits itself in a code of conduct to stop the spread of disinformation. But for politicians, the social network is an exception. Since 2016, the year Trump was elected US President, Facebook has been posting high-news content – such as statements by the President – about its community standards that prohibit hate speech.

Since 2019, Facebook has even explicitly allowed political lies. Political speech is a necessary form of freedom of expression, even if it contains falsehoods. On Facebook, this applies not only to regular posts but also to advertising content, which Facebook provides more reach for against payment. The company refuses to remove Trump’s sponsored video about Biden. It is “not our job to interfere when politicians speak,” said Facebook communications chief Nick Clegg.

The group only wants to intervene if there is a “risk of damage” – for example, by calling for violence. Facebook wants to decide whether this is true. Trump previously caused a sensation with a Facebook advertising warning of an “invasion” by illegal immigration, which was also used in right-wing conspiracy forums and by the El Paso assassin.

Facebook still sees no problem in Trump advertising; the Republican can also spread inflammatory and untrue claims. With his attitude, Facebook is likely to find applause from Trump’s friends from all over the world.

Step three: pens with troll armies confusion

Wrong and misleading information is a powerful tool in politics. It is often not a question of actually convincing people of the claims or a message. Instead, the goal is simply to distract from something else or create uncertainty. For this purpose, specific hashtags or discussion forums are deliberately flooded with incorrect information on social media.

One example is the white helmets in Syria. The volunteer organization provides humanitarian aid in the Syrian war zone, but the helpers are always the target of political attacks.

Russian state media accuse the white helmets of falsifying or even committing reports of atrocities committed by the Syrian regime. The European Union’s External Action Service has documented and invalidated many of the stories.

A network of accounts spreads criticism of the white helmets on social media. The network is supported and strengthened by Russian and Iranian state media, scientists from the University of Washington report in a current paper.

Criticism of the white helmets now dominates on Twitter and Youtube. A small number of accounts manage to drown out positive representations of the white helmets. In doing so, they successfully stir up doubts about the aid organization.

Facebook, Youtube and Twitter have been promising to deal with such disinformation for years. Twitter banned sponsored posts from state media; Facebook wants to mark their pages from November at least.

The two companies recently deleted numerous fake accounts. Your action is directed against “coordinated inauthentic behavior”. How successful Facebook is in doing so is unclear; however, as the company hinders access for scientists despite promises to the contrary.

From the Expert’s point of view, the actions of the corporations fall short anyway. Twitter and Facebook block bots and accounts registered under a false name, as well as those of governmental actors from abroad that specifically target disinformation. But with a network like the one that attacks the white helmets, only a small part is controlled from abroad, according to the study by the University of Washington.

Targeted campaigns often mingled with organic support from extreme right-wing groups and volunteers – a real troll army accompanied by a few shepherds. It makes little sense to see disinformation merely as a problem-controlled influence.

Troll armies are a secret weapon for political campaigns. In Germany, there have already been coordinated attacks from the AfD environment. A CDU politician received hundreds of aggressive posts on Facebook last year after an AfD sympathizer page called to leave him “a nice comment”. However, our research showed that the AfD uses Twitter spammer methods to breed Twitter accounts and is suspected of being behind networks of fake accounts.

Step four: let sock puppets speak for you

There are many good reasons not to be found online under your name. But is anonymity also okay for people who exert political influence with millions of euros?

For example, in January, a previously unknown pro-Brexit group called Britain’s Future in the UK spent £ 88,000 on Facebook ads in a short space of time. The ads pushed for a rapid exit from the EU. Who funded the advertising?

Long description

Who paid for this ad? The trail leads to Boris Johnson. The public domain of Facebook

With classic political advertising, it is usually clear who is behind it – the respective party and a candidate. But Facebook makes it practically easy for everyone to get involved in politics in advertising. As a result, in the 2016 US election campaign, anonymous advertisers paid in rubles.

Facebook now prohibits political advertising across national borders, but advertising-funded from unknown sources continues to exist: In the British case, it turned out that “Britain’s Future” is controlled by a lobby group that is now close to Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Politicians could do the same for the group in the future. With sock puppets, vast sums of money can be invested in advertising on Facebook without having to justify the content – or explain the origin of the funds.

An interesting example is provided by the Zoom research platform, which caused a stir in the Austrian election campaign. Shortly before the election in September, Zoom published several articles on allegedly dubious connections between ÖVP boss Sebastian Kurz and businessman Martin Ho.

Zoom took over an older page for its Facebook presence, which until then posted humorous criticism of the former head of the Austrian right-wing party FPÖ. Her name: “Can this soulless brick have more friends than HC Strache?” The site already had tens of thousands of fans – Zoom almost seized a huge audience overnight.

The creator of the platform initially hid behind a Swiss club; his real name was unknown. After a few days, “Zoom” turned out to be a project of a lone political warrior, the alleged revelations remained less explosive.

The project raises interesting questions: How far does Facebook go to protect the anonymity of political actors? In an earlier Austrian election campaign, groups also appeared that turned out to be sock puppets for political opponents.

Since then, Facebook has tightened the obligations for site operators. Pages must state when they were created and where their operators are mostly located. However, the social network refuses to enforce the imprint obligation for Facebook pages that applies to all websites. Political Facebook pages like @ kaerntnerstraße with over 2,000 subscribers can, therefore, continue to use “satan.com” as contact information without fear of sanctions.

Facebook announced new rules. Accordingly, pages should in future provide information on the “confirmed page owner”. However, this only applies from January and only for political advertising customers in the USA.

Facebook thus sets a strange double standard. The social network forces its users to use their real names in their terms of use. (Facebook calls this “the same name […] that you also use in real life”.) Shouldn’t the same also apply to site operators, especially if they place political advertisements?

Admittedly, the internet companies are taking steps in the right direction. Facebook, Twitter and Google launched archives for political advertising after significant pressure from politics and civil society. They make advertising on the platforms visible to everyone and searchable for keywords. They show who the target audience of an advertisement was and how much it cost.

But Facebook disappointed hopes for full transparency. Facebook and the other companies find it challenging to define what political advertising is, criticize researchers from the University of Amsterdam in a new paper on the archives. It is also still possible for ad buyers to hide the origin of their money and who they are targeting with ads.

Facebook remains a gateway for Donald Trumps around the world and their dirty money. Perfect targeting, sanctioned political lies, space for troll armies and sock puppets – these tactics by right-wing politicians and authoritarian governments are not only possible on Facebook, but even part of the business model.